Pierre Antoine

Pierre Antoine

Pierre Antoine

Pierre Antoine

In 1939, Jeanne Bucher met the 25-year-old Russian painter Nicolas de Staël. Shaken by history and marked by family tragedies, he had already traveled extensively before settling in Paris: he had fled the October Revolution with his family in 1919, lost both father and mother in the years that followed, and found refuge with a Brussels family, the Friceros, who were responsible for his upbringing. His early passion for painting led him, against the advice of his adoptive father, to attend the Beaux-Arts in Brussels, then to travel in France, Spain and Morocco where, in 1937, he met Jeanne Guillou, an artist five years his senior, who left her husband for him. The lovers then traveled to Italy, before settling in Paris, where Nicolas worked hard and destroyed almost as much, spending some time at Fernand Léger’s Academy. After volunteering for the Foreign Legion, he joined Jeanne in Nice. It was here that he met many artists, including the Delaunays, Arp and above all Magnelli. The couple survived thanks to Jeanne’s painting, and in 1942 welcomed a little girl, Anne. The following year, they returned to Paris, destitute and housed thanks to the generosity of Jeanne Bucher, who supported them and bought Staël his first drawings in 1943.

It was in 1944 that Jeanne Bucher exhibited the artist for the first time, alongside Domela and Kandinsky. Nicolas de Staël’s first solo show at the gallery took place a year later, in 1945; it was then that some collectors began to take an interest in Staël’s work, of which Jeanne Bucher wrote that “among the young (…), there are above all Lapicque, Estève and Bazaine. I like Lanskoy and Nicolas de Staël the most, as they are the most abstract, following neither Matisse nor Bonnard, nor even Picasso”. After his figurative beginnings, de Staël moved on to abstract compositions in 1942, marked by a dark palette that would never cease to evolve, as the artist pursued an ever more personal quest throughout his career. Over the course of the ’40s, for example, the colors became lighter, the panels wider and the paste thicker on the canvas surface. The artist, naturalized French in 1948, became an increasingly famous painter, whose works were snapped up by Americans and sold by his New York dealer Rosenberg, even entering the collections of the MOMA in 1951, a year after the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris had first acquired them. Jeanne, exhausted, died in 1946, but the painter was able to regain emotional stability with Françoise, with whom he would have 3 children. His attention to light is increasingly evident, his science of composition retains its precision and his intense production makes him one of the major leaders of European abstraction, beyond the reductive classifications of the Ecole de Paris or informal art.

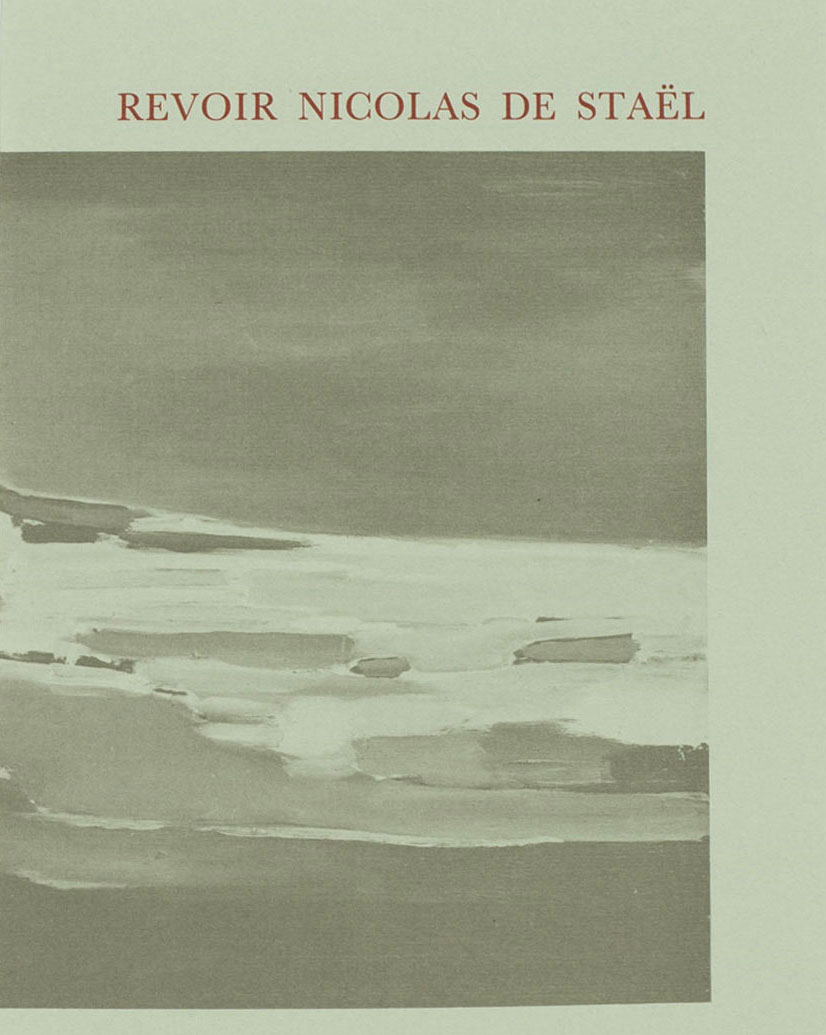

However, Staël encountered incomprehension when the figure made a comeback in his work: the famous painting Les Footballeurs (1952), which followed a match the artist attended at the Parc des Princes, earned him the wrath of the proponents of abstraction, who did not forgive him for what they considered to be perjury. Fascinated by the interplay of color and movement on the field, Staël opened up a path that put the two major trends in art of the time back to back, explaining: “I don’t oppose abstract painting to figurative painting. A painting should be both abstract and figurative.” Music also played a key role in these years, as evidenced by such major paintings as Les Musiciens, L’Orchestre and Les Indes galantes. The following year, in 1953, the artist settled in the light of Ménerbes and traveled to Italy, where he painted the brilliant colors in some of his most famous canvases (the Agrigento series). He didn’t travel alone, but with a woman he had fallen madly in love with, Jeanne Polgue-Mathieu: the nudes he painted reflected his passion for the young woman. It was also in these years that the impasto of his canvases gave way to a more fluid material, which once again baffled some of his admirers and collectors, who were also taken aback by the numerous seascapes that occupied the artist’s time, as he sought a possible outlet for a love that seemed less shared by his muse. What happened next is well known, and quickly took on the trappings of legend: the artist’s suicide, when he threw himself from his Antibes studio, colored his destiny without obscuring his growing importance in the history of art.

Jean-François Jaeger’s encounter with de Staël’s art and his “light irreducible to any other” had been a turning point in his career. In early 1958, a group of 43 works on paper, charcoal, wash and Indian ink honored the memory of the artist who had died three years earlier.

A large number of monographic exhibitions were subsequently devoted to the artist, including those at the Fondation Maeght in 1972 and 1991, a vibrant tribute by the gallery on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of his death, at the FIAC 1985, and major retrospectives at the Grand Palais in 1981, the MNAM in 2003 and the Fondation Gianadda in 2010. A Catalogue Raisonné of his paintings will be published in 1997, and a catalog of his works on paper in 2013, on the occasion of a new exhibition by the gallery.

The Passion de l’Art – Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger depuis 1925 exhibition at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence in 2017, the first retrospective devoted to the gallery and co-curated by Véronique Jaeger, featured essential works by the artist, testifying to her regular presence in many of the gallery’s exhibitions.

In 2023-2024, the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, in partnership with the Fondation de l’Hermitage in Lausanne, is devoting a retrospective exhibition to Nicolas de Staël, to which the gallery is contributing significant loans.